Is your Warehouse Layout Up to Date? Receive an Updated Layout in 2 Weeks.

Optimizing Your Distribution Network: Calculating True Capacity in Warehouse Design

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David Beaudet has been helping companies maximize warehouse capacity and make better distribution infrastructure decisions since 2004. His consulting experience spans many industries including food, pharmaceuticals, apparel and spare parts. He is a regular speaker on topics relating to distribution centre design.

Optimizing Warehouse Capacity

Capacity is one of the most fundamental concepts in a warehouse’s design. But what does capacity truly mean in the context of your distribution operations? It’s not as simple as quoting a number of pallet spaces or the total cubic volume in your building. Knowing how to define true capacity, how to calculate it, how much excess you should have to operate and what to do when you don’t have enough, plays a fundamental role in designing your warehouse and optimizing your distribution network.

Different stakeholders define warehouse capacity in diverse ways, depending on why and how they view the facility:

- Buyers look for empty space to fill with inventory and new listings

- Distribution Centre (DC) managers look for flexibility to execute efficient operations

- Owners look to maximize the return on the distribution asset in which they invested through a lease or purchase

These stakeholders need a common approach to understanding capacity if they want to strike a balance between their competing needs, or at least agree on when it’s time to address a capacity problem or plan for growth.

I. Calculating Your Warehouse’s Capacity

The Three Dimensions of Capacity

The capacity of a distribution centre has three dimensions: storage, throughput and slotting. A warehouse reaches full capacity in each dimension independently, though limitations in one often will affect the others.

We can define each dimension as follows:

Warehouse Slotting Capacity – the number of pick locations that can be provided to support an operation’s active stock-keeping units (SKU) base.

The number of pick facings is limited by the materials handling infrastructure that supports the pick line. A well-engineered pick line provides locations sized to individual SKU requirements, balancing excessive travel during picking against frequent replenishments to restock locations. Usually, when the number of active SKUs increases, the size of locations on the pick line must be reduced to make room for new items.

As the size of locations gets smaller, replenishment tasks and picker congestion increase, leading to lower operating productivity.

Storage Capacity – the amount of physical inventory that can be stored within the warehouse. This is a function of the total number of storage locations within the DC and the size of these locations. It is important to distinguish between the gross storage capacity and the operating capacity of a facility.

- Gross storage capacity represents the capacity if every location were full – a theoretical capacity that cannot be achieved in reality.

- Operating storage capacity is the realistic capacity of the warehouse that accounts for operating constraints, such as the need to put away receipts into open locations, and physical constraints, such as the inability for product to perfectly fill any given location.

Throughput Capacity – the handling volume of the distribution centre. It represents how many orders, lines, cases and units a warehouse can receive or ship over a given period of time. Typically, throughput capacity is limited by bottlenecks that arise from space and infrastructure limitations. These bottlenecks first appear during peak periods and then, as volumes increase, become chronic constraints.

Uncovering Operating Penalties: KPIs for Your Warehouse

While some indicators of capacity shortages may be obvious (e.g., there’s not enough space to put away pallets), others can be more difficult to detect (e.g., the pick line is too short to place each SKU in its ideal slot size).

When a distribution centre ignores such indicators and operates beyond capacity, it pays clear and hidden operating penalties. By tracking capacity related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), you can identify these penalties and act rapidly to address them.

Here are some KPIs related to your warehouse’s capacity:

1. SKU-to-slot size assignments

Measurement: Replenishment instances per week per SKU

General Rule: Re-slot SKUs generating more than one replenishment task per day (fast movers) or per week (medium/slow movers)

2. Storage capacity utilization

Measurement: Pallets on hand vs. pallet positions and Cubic feet on hand vs. net cubic feet capacity

Target: Keep 15% open reserve pallet spaces to facilitate putaway and replenishment (the amount is a function of inventory turns)

3. Pick slot utilization

Measurement: SKUs vs. pick slots

Target: Keep 10% open pick slots to easily introduce new SKUs or provide a buffer during peak periods

4. Dock-to-stock time

Measurement: Delay between receipt and putaway times

Target: Reduce over time

5. Damages & mispicks

Measurement: Rate as a percentage of units picked

Target: Minimize over time

6. Throughput productivity

Measurement: Units per hour, using the handling unit as the proper unit of measure

Target: Improve over time

Any KPI trending in the wrong direction indicates a capacity problem. But not all capacity problems entail that you should be hunting for a bigger, taller building right away. The overall goal, when addressing your capacity issues, is to optimize your distribution network while you maximize your ROI. Sometimes, improving space configuration within your current installations is going to be the best solution to achieve that goal.

If you find your KPIs declining, identify and explain the capacity elements hurting your ability to operate efficiently. Here are some potential reasons you might be having trouble with capacity in your DC:

| Symptom | Potential Capacity Issue |

| Increasing number of replenishment tasks per SKU | ˃ SKUs are assigned to pick slots that are too small ˃ Pick line is too short |

| Less than ideal open reserve slots | ˃ Incorrectly profiled reserve locations ˃ Footprint is too small or clear stacking height is too low |

| Less than ideal open picks slots | ˃ SKUs are assigned to pick slots that are too large ˃ Pick line is too short |

| Increasing dock-to-stock time | ˃ Insufficient dock space ˃ Not enough open reserve locations ˃ Congested aisles |

| Increasing damages and mispicks | ˃ Unergonomic pick slots ˃ Deficient slotting and sequencing ˃ SKUs crammed in slots too small ˃ Similar SKUs slotted next to each other ˃ Warehouse management system, or lack thereof, not set up properly |

| Production levels stall, even with additional labour | ˃ Poorly distributed workload across zones ˃ Congested aisles |

| Decreasing productivity | ˃ All of the above! |

II. Know Your Supply Chain Strategy, Know Your Warehouse Capacity Needs

Your KPIs point to a capacity problem. Now, before you start looking for a solution, you must determine your strategic goals and assess your current and future needs.

Create a Baseline

A distribution centre is a dynamic environment with volume peaks and an ever-changing SKU base. While this might make it hard to determine your slotting needs once and for all, it doesn’t make it impossible. For design purposes, what we need is to frame a baseline that adequately represents your current operations, that is: a description of the characteristics of an average week during a peak period of activity. Taking an average during a peak period ensures that capacity calculations cover most weeks throughout the year without oversizing for the peak week. The baseline should describe the active SKU base, quantities shipped and average inventory levels.

Plan for Growth

To plan a facility for the future, you must estimate how the operation will change in the future. Consider what changes might come in the following growth parameters:

- Sales – an increase in sales affects throughput and the pick line

- Variety – an increase in variety affects the pick line

- Inventory – an increase or decrease in inventory turns affects storage

The appropriate strategy is to aim for about five years of usage out of the upgraded infrastructure once all changes are in place. This means looking six to seven years down the road when you first set out to define your capacity needs. The objective is to balance the elapsed time between large scale projects – not so short that the workforce feels it is constantly in the middle of significant changes – and the capital investment – not so large that you are unable to achieve the expected ROI.

So, consult your crystal ball – or those in charge of defining sales projections, depending on your style – and apply these expected changes to your original baseline. Your warehouse’s capacity requirements must be calculated by taking into account the forecasted growth of your supply chain.

Size Your Warehouse Picking Operations

In order to get a clear picture of your warehouse’s slotting capacity, you must take a close look at your picking operations. Many supply chains grapple with SKU proliferation while working to lower inventory levels. The result is that pick lines – the size and arrangement of locations to pick from – have become more important in determining warehouse space requirements, often more so than storage needs.

There are three fundamental aspects to sizing a pick line:

- Each item normally requires a dedicated slot along the pick line sized to balance keeping the pick line as short as possible while avoiding excessive replenishment activity.

- A picking and order assembly strategy that minimizes labour and completes the order within the time frame set by customer service.

- The sequencing of product such that the distribution centre delivers assembled orders in a stable, product-sensitive way (e.g., no crushables on the bottom of a pallet)

What you want is to strike the perfect balance between picking and replenishment labor. In order to achieve that goal, you should assign a type of material handling equipment and a slot size to every single SKU, considering the item’s velocity, inventory profile and dimensions. Combining these SKU-level needs determines the length and configuration of the pick line(s).

Size Your Warehouse Storage, Gross and Net

Capacity expressed in cubic volume is the most accurate representation of what a facility can store. However, it is impossible to use 100% of your warehouse’s gross storage capacity unless your distribution centre receives and ships nothing. The art and science of determining your true storage requirements come from properly matching the inventory you have to appropriate storage types.

Let’s take a closer look at how LIDD calculates true storage capacity.

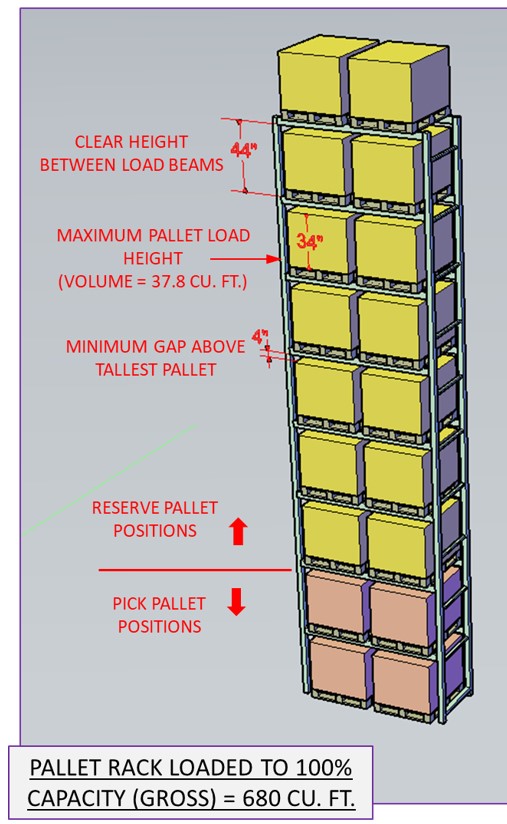

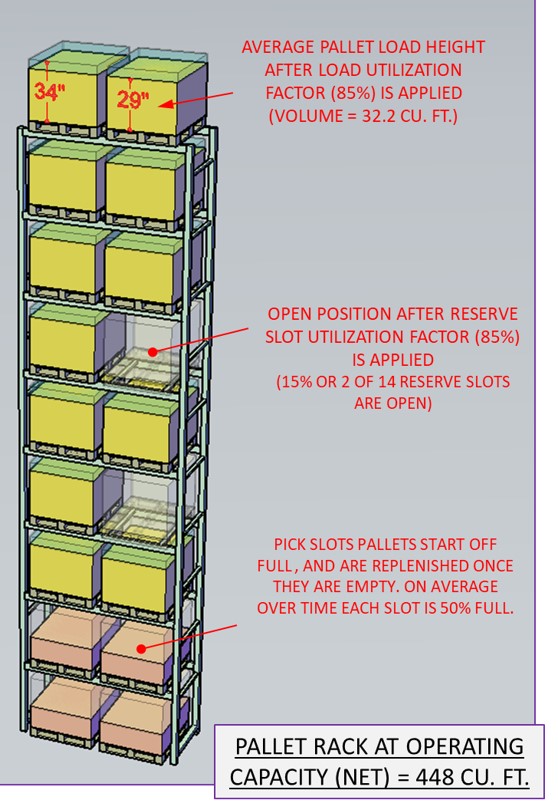

The Inoperable Gross Capacity

- All loaded pallet heights are a perfect match with the maximum slot opening heights. It includes a 4” gap between top of product and the load beam above.

- Every pallet position holds a pallet.

Keep in mind that this state does not and should not exist in a working distribution centre. There are various reasons for that.

One reason is that most DCs hold a variety of SKUs, which means that there will be a need for multiple pallet heights. Accordingly, load beams should be installed to create openings that are a good match with each pallet height. If you were to perfectly adjust slot heights to each SKU, you could theoretically bring your loss in volume to a minimum. However, by creating so many differing “custom” slot heights, you would significantly reduce your slotting flexibility. Even if that were not an issue, if every slot were filled to minimize volume loss, then your picking labor would find itself with insufficient operating space. It would eventually also make it impossible for your warehouse to accommodate your growing business and new SKUs.

Calculating Operating (Net) Capacity

Properly understanding operating capacity is critical to a DC’s operations. Although it is always possible to go over that threshold, doing so will inevitably incur operating penalties. As we have already seen, not only will it significantly impact its overall performance, it will also severely reduce its capacity for growth.

Various methods exist to calculate and express the cubic volume that represents a warehouse’s true storage capacity. At LIDD, our engineering experts have determined that the following guidelines provide the best results:

- Calculate the gross capacity for every slot: length * width * height of area which can hold product.

- To account for variety in pallet heights, apply an 85% utilization factor to the capacity of the tallest loaded pallet that can be stored in each slot. This factor also covers loss in volume due to any spaces between stacked cases that might occur.

- Apply the second 85% factor to allow for open reserve slots. To handle product there must always be open slots in pallet rack reserve positions. Our data shows that 15% open slots provide the best results. Fewer open slots begins to negatively affect productivity.

- For pick positions, apply a 50% utilization factor. These pick slots go from full to empty. On average over time they are half full.

You may therefore determine your true storage needs by following these steps:

- Calculate the operating capacity provided by the equipment supporting the pick line.

- Compare your projected inventory to the calculated net capacity. Does it fit?

- Whether you need to add single deep or double deep racking, drive-in racks or bulk space depends on the profile of the excess inventory that does not fit in the pick line.

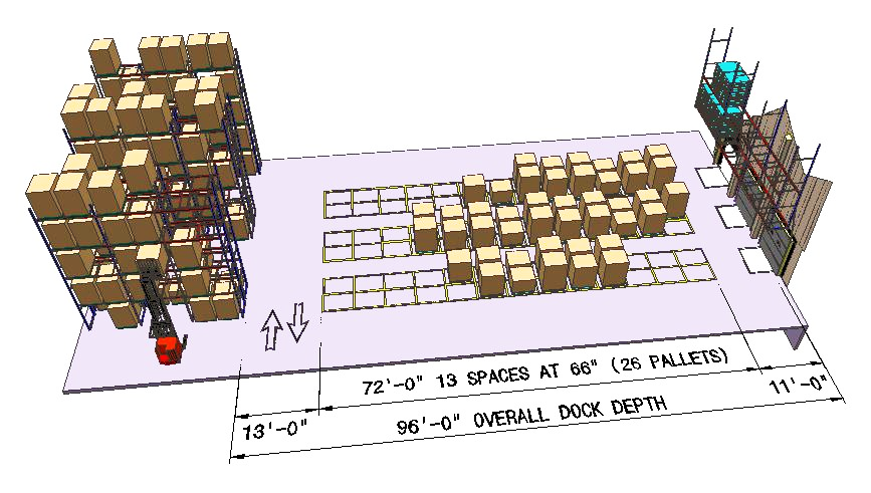

Size Your Operating Space and Warehouse Dock

Maximizing the use of your warehouse’s gross storage capacity is tempting. You have invested a lot in your DC and you want to make the most of it. Following that logic, you might think of the empty spaces that result from net storage capacity as losses you should try to avoid. However, when a distribution centre functions beyond its net capacity, it unavoidably sees a reduction of its working space and pays the price in throughput capacity. As inbound and outbound pallets begin to clog operating aisles, slowing movement through the warehouse down to a crawl, it becomes more and more difficult, if not impossible, to access items in the racking.

For a DC to function properly, it needs some empty working space to receive, stage and move product within the storage area, as well as pick product, pack and stage outbound orders. Remember that this labour requires equipment with minimum operating widths and turning radii; there must be enough empty space to operate adequately and meet expected productivity rates.

Congestion is corrosive to a DC’s productivity. Gridlock is the distribution centre’s death knell. To avoid it, you must secure sufficient space to complete the number of hourly tasks by function – across all functions. You will need, for example, to have aisles that are sufficiently large for your equipment to operate unencumbered.

Shallow docks is one of the most common mistakes we encounter in warehouse design when people blindly set out to maximize storage space. While different distribution operations will often need different dock configurations, all should keep in mind the following considerations:

- You should be able to unload and stage your largest inbound load without spilling over to adjacent doors.

- The space between each staged pallet should be sufficient so that receivers can access all sides.

- Allow room for a two-way travel aisle between dock staging and storage racks.

- Incorporate more space if specific requirements warrant it (e.g. reverse line picking)

Some will argue, not without reasons, that these guidelines result in too much dock space. Streamlining processes in the DC, the argument goes, will allow you to function adequately with a smaller dock. Of course, streamlining your operations should always be a priority. But a million square feet of storage space will not count for much if the dock is frequently congested. That is why it has become common practice in the field to design an 80’ to a 100’ deep dock in high volume environments such as food distribution.

Your warehouse may not need such a deep dock. But, regardless of your operations’ volume, the dock is and always will be the heart of your distribution centre. While it might make financial sense today to maximize storage density in your warehouse by keeping your dock’s size to a minimum, that decision could prove costly tomorrow when your sales have grown and you’ve successfully developed a high turn business.

III. The Roadmap to Solving Warehouse Capacity Issues

Consider Project Commissioning

It’s important to understand and measure your true current and future capacity needs before you try to solve your capacity issues. If it turns out that all you need are changes to equipment, processes, or inventory management strategies, you will be able to address your capacity issues in your current facility. But if those improvements are not enough, a facility expansion or a move to a new building may be necessary. Whatever the case may be, one thing is certain: solving your warehouse capacity issues will require significant investments in both time and capital.

In general, a distribution company does not have staff members on board with the necessary knowledge and experience to efficiently lead it through the whole process. Even if it did, the amount of time required by such a project will make it impossible for staff members to both oversee the transition and maintain their normal activities in your supply chain operations, leading to additional operating penalties.

Hiring a project commissioner, such as LIDD, as early as possible in the process is a great way to avoid such operating penalties and protect your capital. A commissioner has the knowledge, both theoretical and practical, to efficiently guide you through your transition towards a renovated or a newly acquired facility. That person will also be entirely dedicated to your project, overseeing each of its many stages with a comprehensive view, leaving your operations staff free to perform their regular duties. As a result, we find that the cost of investing in project commissioning is generally offset by the financial penalties he or she will help avoid along the way.

Ultimately, whether you opt for a project commissioner or not, you should always plan the roadmap to solving your warehouse capacity issues with the optimization of your distribution network and the maximization of your ROI in mind.

Reset, Expand, Move: What does your supply chain need?

The gap between your true capacity needs and your facility’s size and configuration dictates when significant changes must take place.

If capacity issues in your current warehouse do not threaten your ability to operate properly in the foreseeable future, direct your planning efforts to redesign existing space. The goal is to match your layout, equipment and operating systems with the requirements posed by each dimension of capacity.

However, if your facility is already bursting at the seams, and projected growth will only make matters worse, an expansion or a move should be your main focus.

Each alternative brings a set of specific challenges:

- Reengineering existing space

- Resetting existing space implies temporarily “losing” capacity. How will you operate while implementing changes?

- Expanding the facility

- While expanding offers the luxury of creating a larger footprint to occupy, the final design shouldn’t be just an “add-on.” Rather, the configuration and resulting flows of the final state must create a single, unified operation – something easier said than done.

- Moving to a new building

- If you can’t perform a hard cutover (i.e. transition over a single weekend), you may have to operate two sites for a period of time. This creates labour issues and complicates the I.T. strategy.

One challenge holds true regardless of the approach that suits your situation: you need to involve the right stakeholders if you are going to reap the benefits of augmented capacity.

Gather All Stakeholders

Numerous parties play a role in the planning and execution phases of a major operational change. It might be tempting to delay some stakeholders’ involvement until later in order to streamline the process. But this creates the risk of having to revise your plans midway if a legitimate omission (say, not planning for enough charging stations) or a design flaw (the column spacing does not permit the minimum required aisle width) is uncovered during the approval stage. A project commissioner’s expertise and experience can help with the early coordination of all involved parties. Achieving that coordination will significantly reduce the chances of costly revisions midway through the operational changes.

Every stakeholder has expertise and valuable experience which must be incorporated in the design of the solution. Therefore, gather all internal and external resources at the beginning of the project, present the strategy and ask everyone to highlight where and how it affects elements under their area of responsibility.

One common planning error is to delay the involvement of I.T. services and assume that the Warehouse Management System will “simply” adapt to the new work methods. More often than not, that assumption will turn out to be wrong. Such a mistake can bring a project to a costly halt until a solution is found – do we change the layout and processes, or do we spend time and money on I.T. development?

As an operations leader, you define the needs, drive the solution and lead the initiative, but the following stakeholders outside Operations are crucial to the planning of a capacity improvement strategy. Get their perspective early to solidify yours. Once all parties have had their say, it’s time to get to the drawing board.

Internal

1. I.T.

- Participate in creating the transition plan

- Consider possible improvements that could be made at the same time

- Run test scenarios

2. Purchasing

- Communicate pallet configuration changes to vendors

- Understand potential future changes in volume or variety

3. Marketing/HR

- Potentially uses storage space for marketing items (promotional items, brochures) or internal HR materials

4. Executives/Finance

- Buy in for investment and risk

External

1. Architect

- Determine impact on structural/electrical/mechanical elements

2. General contractor

- Assess feasibility of proposed changes

3. MHE suppliers

- Validate equipment specifications and installation

- Propose alternatives

Warehouse Design Solutions

With your capacity needs precisely defined and input from all stakeholders, you now have all the elements to develop a solution. As you do, keep in mind that this solution will not only involve changes to equipment and layout, but also potentially modifications in your operating methods as well as adaptations in your software functionality.

Whether or not you should introduce new kinds of material handling equipment and/or modify how you work is a function of various factors, notably:

- How the business has evolved since the last major reset

- Changes in order profiles (e.g. introduction of e-commerce activities)

- Available space (to reset, to expand) and the necessity to increase the density of storage and work areas

- The need to increase throughput capacity

- The implementation of new software (or functions) enabling improved processes

Similarly, as you elaborate layout alternatives that support capacity requirements, don’t forget to account for elements that do not relate directly to inventory and orders, such as:

- Battery charging for mobile equipment

- Storage of packing supplies or other internal supplies

- Lockers and cafeteria

- Offices for operations personnel

- Parking (for trucks in the yard and for employees)

- Any other ancillary services

Regardless of what your immediate strategy may be, always consider how subsequent phases of expansion – in 6 or 7 years – may unfold as you develop your ideal solution. In the food industry, for example, that could mean building a new cooler with freezer floors. While the initial investment might be more significant, it will provide greater flexibility in the future, which turns out to be a clear advantage in an industry with rapidly evolving customer trends.

To evaluate the range of options, you should create a scoring matrix to weigh the pros and cons of feasible solutions the following criteria:

- Ability to support projected capacity needs

- Investment required (capital investment and operating expenses)

- Flexibility towards changing business conditions

- Ease of transition

With the winning solution in hand, the next step will be to come up with a detailed transition plan so that stakeholders can orchestrate their work and plan for required resources. Set a realistic, but aggressive goal to go live, and accept schedule changes only when events happen that are out of your control.

Warehouse Capacity – Final Thoughts

Capacity problems in a distribution centre can be crippling for a business. It is essential to company’s growth to be able to recognize their existence and determine what causes them.

- Calculate your needs in all three dimensions of capacity (storage, throughput and pick line)

˃ Issues in any of these dimensions hurt your operation, and it’s important to understand them individually.

˃ Calculating your needs precisely requires complete, valid data and strong analytical capabilities to ensure that design decisions are based on facts, not gut feelings. - Forecast your future needs based on your current volumes and projected changes to your business

- Elaborate and evaluate solutions to solve capacity problems

˃ Decide which strategy to employ based on how much your needs differ from your current capacity and your planning time horizon

˃ Hire a project commissioner as early as possible in the process: that person’s knowledge and experience will have a significant impact on your ROI.

˃ Have all stakeholders around the table from the start to obtain a complete and coherent perspective. Your team can lay out a detailed plan, minimize the risk of surprises and develop a solid solution with a streamlined approval process.

The course of assessing and planning how to solve capacity issues is just the beginning. An implementation is never easy, but with a well-thought-out design and robust transition plan, you can manage it properly.

Looking for guidance on optimizing your distribution network and managing warehouse capacity? Get in touch with us below.